Old Jacksonboro Road crosses the Savannah Highway within a half hour of Charleston. The name for this intersection is Jericho. It was once the name of a community. Today it is a crossroads on the outskirts of a town called Adams Run.

Jericho was once the site of a hotel, a post office, and a store with gas pumps. The hotel had three stories if one counts the spacious attic with dormer windows and bath. It had exterior wooden stairways, which resembled fire escapes. Around 1964, it was converted to a boys’ home by the Reconnu family. They operated the boys’ home until about 1968.

The store came equipped with a soda vending machine that would allow a mischievous boy to yank a bottle out without paying. The trick to it was not to brag to ones mother about the achievement.

The Mission returned to Carolina in mid-1970 to discover the Hotel Jericho, a bargain for a gastronomical temple, complete with guest suites and a burn pile in the back, all blackened from the last fire and wet from the last rain, with an aroma of metamorphosed plastics, rotting food, and rusted scrap metal.

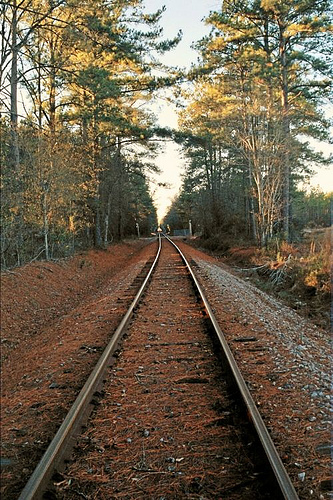

It turned out the Hotel Jericho had too many hidden maintenance and repair issues, and it wasn’t easy to unload. Without sufficient income, the Mission was not able to sustain its Jericho burn-rate for long. In the wink of an eye, they packed up and left the Hotel Jericho for a little trackside house in the hamlet of Ruffin, which is little more than a railroad crossing on the Lowcountry Highway. The Mission wasn’t actually able to sell the Hotel for a couple years after it left Jericho. In the following years, the final solution seemed to have been found when it all burned down in a couple of fires.

The new location did have its luxuries. The day they arrived, Armen and Cindy discovered the new site came with its own playground: a rusty old metal swing set, an old, half-empty bottle of soda complete with an escort of hornets, and a shed in the back.

Every hot, sweaty night, freight trains would thunder by, shaking the house as they passed, and blasting through the cacophony of insect songs. The tracks, with the trestle down the way, were a temptation for wandering feet, haunted by the occasional odd shoe left to seed the imagination of a young boy. The oily, black sleepers seemed laid out to trip up the traveler, and the cool steel rails seemed like blunt blades.

Every bit as terrifying as the rails was the altogether foreign and unnatural experience that is called—with no lack of irony—kindergarten. Armen had hardly been introduced to the terror of mass education when the Mission was compelled to move on to nearby Walterboro, where he was fortunate to attend kindergarten at a small Catholic church just down a dirt road from the Mission.

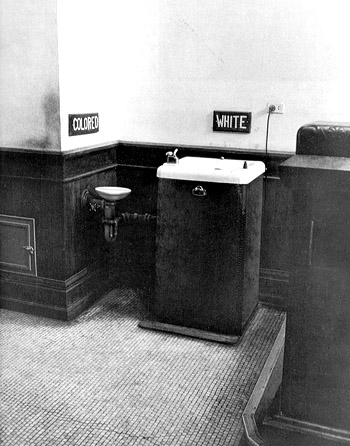

The Mission was at least able to draw in some income at Walterboro, but not enough. The Mission’s kitchen and clinic served all comers. It could hardly afford to turn anyone away, but it was put under more and more pressure to do just that. Serving both whites and negros was an affront to southern whites. The Judge had not come to the South to tell anyone how to live—he had come to celebrate the South, but as an Armenian, it was difficult for him to allow himself to participate in the marginalization of a people.

The Mission was nearly compelled to return to California, but the Judge found an opportunity in the Piedmont. It was on the edge of Appalachia, in an old house with a forested canyon in the backyard, where Armen would sometimes explore. Cindy would occasionally come along, but she would unavoidably fall behind while looking out into the woods or up at the sky. She would sometimes accompany her brother when he would explore the crawl space under the house. When they found some loose bricks in the crawl space, she helped him rearrange the bricks to resemble a miniature house. The partnership ended, however, when Armen began to build small fires in their brick fortress. Cindy did not share Armen’s fondness for fire. In fact, she expressed a mortal dread of the smallest flame. It was another one of her quirks that her adoptive parents imagined might have been acquired during her time in Istanbul. At the Mission, she seemed most at home in front of the small black-and-white TV set watching westerns. She seemed transfixed by the Indians in particular.

As passionate as the Judge had become about soul food, he couldn’t manage to make a living selling soul food as food for the soul to Southerners. He’d extended and enhanced the culinary experience in unique ways, but the fact that he was a Yankee in Southern eyes seemed to always get in the way. He didn’t think of himself as a Yankee; he saw himself as an Armenian and a Fresnan and an American, but he began to realize that how he saw himself didn’t matter in the South. Recognizing this, leaks began to break through his resolve. He thought about how long it had been since he’d listened to a Giants game on KSFO. He thought about the dry bake of the Fresno summer air, and the cool, moist blanket of the Tule fog. Hearing that Willie Mays had been traded away to the New York Mets was the last straw. The Judge resolved to return to California this time as a Californian. For the first time, this would mean coming home. The Mission was packed up under an evening thunder storm, just after the mess from Cindy’s fifth birthday party was cleaned up. Kale ran off, tale between legs, to make a mess of his own in the basement. The showers fell harder, mixed with hail and with shorter intermissions, until the Mission set float and began its drift westward.

©2008 Dan J. Jensen