Sol rules the sky,

a celestial Medusa,

flames swinging and waving out into space

like so many yellow snakes,

the failure of the metaphor being

that we may look upon him,

though only through his companion;

a month being nothing more

than the time we must wait

to see the fire of heaven

as he sees himself, fully,

in his mirror

of wounded stone.

Tag Archives: fire

Kindling

Chainsaw gardeners everywhere

believe gardening to be

the practice of keeping

the greenery away

from the path,

while deadwood

accumulates within,

where gardener and pedestrian

dare not stray,

the garden itself

slowly aging

into a woodpile,

waiting not for spring

but for fire.

Limbs

What some men seek

in haunted attics, others find

on abandoned trails,

the old man replied.

In the aftermath of an inferno,

amid the ash, baked soil,

blackened granite,

the fire-scalped ridge,

I greeted the naked skeleton

of an old pine with a hand,

and forgetting my brutishness,

broke off a scalded humerus,

heavy with marrow

and unspent fire.

Having taken life, weak with shame,

I avowed her disembodied limb

to be my companion, and timber

and flesh strode away

through canyon and stream,

arm in arm.

I’m blind now, obviously

Beautiful, I don’t know how

Your smile became an ocean wave,

Tumbling everything over

And over with

Crushing saltwater power,

Your eyes, binary suns

Burning through the world, and

I’m blind now, obviously,

But the heat remains,

Washing through your hair

A whispering

Autumn breeze

Through the shivering

Aspen, somehow,

Beautiful.

Sacraments

I am serious about my religion.

I don’t take its sacraments lightly.

They may cause you discomfort:

A long walk, a trusted companion, an open fire.

I cannot imagine a relic, a book, or a doctrine more sacred.

Perhaps you doubt them.

Perhaps I doubt yours.

A walk through a wood

A walk through a world

A friend

“Man’s best friend”

A crackling campfire

“The most tolerable third party”

A sworn companion

The Logos fire

Henry David Thoreau

A boiling star

The Hungriness of Stuff

We previously reflected upon the intimate, multifaceted relationship between ancient man and fire, and considered how easy it would have been for a man such as Heraclitus to conceive of the idea that fire is the fundamental constituent of all matter.

Heraclitus was, after all, a subject of the Persian Empire, a land of fire worship, and the reputed cradle of alchemy. Alchemy is a practice of transmuting matter that depends greatly upon fire. It seems to be a natural—albeit mystical—offspring of the bronze age.

Perhaps after recognizing the ubiquity of fire, Heraclitus reflected upon the nature of fire, and came to this conclusion:

fire is hunger and satiety.

—Heraclitus

Fire is indeed a hungry phenomenon. It seems to exist exclusively to consume, though the light and heat it has provided us through the millennia make it much more than a consumer. Yet it remains an archetype of consumption. Is not combustion the primal hunger within us? Is it not our deepest physiological craving for the fuels of combustion: oxygen and carbon compounds?

But fire is obviously not equal to hunger, for as consumption, it is also the satisfaction of its hunger.

Seeing everything around us as governed by this paradox, one can easily see the function of fire in the philosophy of Heraclitus. Heraclitus taught that the world is governed by a harmony of opposites. Recognizing that harmony, he saw wisdom in the working of things, but it was a harmony of war, of hunger. Whatever equilibrium he could see was a dynamic, cyclic equilibrium under tension. To Heraclitus, fire must have seemed fundamental both literally and metaphorically.

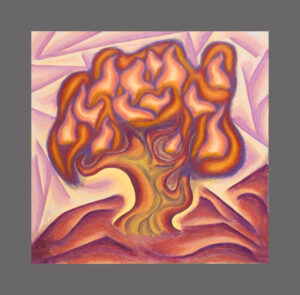

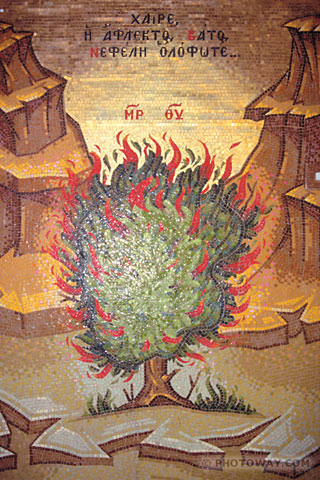

The Burning Bush

When God spoke to Moses, God took the form of a burning bush.

Why did an ancient Israelite think that God would take the form of a self-immolating bush?

It might be natural enough to think that fire consumes a bush, but there’s another way to see it—the way that many ancients saw it: the fire is in the bush from the beginning. It’s not really such a crazy idea if one considers that the fire cannot occur without what’s in the bush. Sure, the fire also needs oxygen, but again: the bush exhales oxygen as it generates wood and foliage. It provides the fire with everything it needs. It is, in a real sense, a terrestrial offspring of the sun, waiting to ignite.

With the igneous nature of vegetation in mind, consider the igneous nature of the earth. Volcanoes could not have escaped the awareness of the ancients. With accompanying seismic activity, it must have been easy to conclude that the earth itself has a fiery cauldron at its heart. Gas and oil seeps, when ignited, may have lent some corroboration to this conclusion. Indeed, it is well-known that a fire temple recently made use of the natural gas seeps at Baku, Azerbaijan.

The Biology of Fire

What is the color of life?

Green. Certainly, most observers would agree.

Yet when one considers what the green represents, one might not remain so certain. Green is the color of photosynthesis. It is therefore the color of the conversion of light energy to chemical potential energy—stored energy.

Isn’t life better seen as the active changes in things, rather than the potential for those things to change? What life would there be if nothing ever actually changed?

Life itself is in the consumption of the potential—the combustion of the products of photosynthesis. The actual life is in the burning, that is, the respiration.

A fire seems alive. It respires just as we do, needing the same oxygen and exhaling the same carbon dioxide. it is that same phenomenon—combustion, in the form of cellular respiration, that gives us life as aerobic creatures.

Not to take anything away from water or carbon, which to some extent all life seems to require; it’s specifically combustion that gives us life. Of course fire is a universal phenomenon of which combustion is but one example. Ultimately, it is fire that gives us the building blocks of life—elements such as oxygen and carbon; but for now let us stick with combustion.

The food that we consume is used to feed the internal combustion engine within us, just as a campfire consumes wood; just as a car’s internal combustion engine consumes petroleum. Like the life that we know, the fire grows as it consumes, and as it grows, it travels. Not only does an individual fire grow; some even bear children: they spit out fire children that rise on the parents’ convective currents and fly outward to begin lives of their own.

Perhaps you have seen a fire sleep, mimicking the stars in the sky with its constellations of red coals. Or maybe you’ve watched the mesmerizing dance of a fire. Maybe you listened to its crackling song while it danced. Was it a song, or was that the sound of its infernal molars crushing its food? Did you hear it breathe? It breathes in and it breathes out.

Have you ever suffocated a fire? Funny how that can seem a little like a killing.

The Hexad of Wisdom

In Zoroastrianism, the benevolent Lord Wisdom interacts with his creation through six gods—or principles—of his making. These can be thought of as the pillars of Zoroastrianism:

-

Good Thinking. “Good” is regarded in two senses: both as beneficial and as effective. Thus wisdom and goodwill are implied. This “good thinking” is the means by which men are advised by Lord Wisdom.

-

Truth. This is Asha, the most valued principle in Zoroastrianism. Asha is symbolized by fire, probably for fire’s utility in illumination, prehistoric trials by ordeal, and in purifying metals. Asha is generally translated as “righteousness”, but seeing as Asha is generally juxtaposed against “the Lie” in the earliest sources, it probably originates more in truth rather than in obedience to a moral code.

-

Reform. This is often described as “desirable kingdom,” indicating the core objective of Zoroastrianism: world reform. This notion might also be expressed more generally as “order,” which is how Plutarch interpreted it. Thinking of it as order, we can easily see why this principle is closely associated with the heavens. Seeing it this way, “reform” can be depicted as bringing the orderliness of the heavens down to earth, hence the Kingdom of Heaven on Earth, or as my Bahá’í friends say, “the New Order” or “World Order.” Plutarch describes this Zoroastrian “kingdom” as follows:

Then shall the earth become a level plain, and there shall be one manner of life and one form of government for a blessed people who shall all speak one tongue.

I don’t think it’s too much of a stretch to interpret “a level plain” politically, rather than physically. Additionally, the principle of world reform need not entail notions of theocratic utopias. The point, I think, is to make a project of ridding the world of suffering.

-

Devotion. This is generally seen in a conventional religious sense, but when we consider that this god of devotion often doubles as a Mother Earth figure, we can see that “devotion” in this usage can be seen as a loving commitment to the welfare of the world.

-

Health. Symbolized by water. Coupled with #6 (see below). Sometimes cast as wholeness.

-

Life. Symbolized by vegetation. Generally specified as immortality or long life. Along with #5, this is often presented as a reward to the righteous. I prefer to think of health and life as values. This is not far-fetched, considering the emphasis placed upon life in Zoroastrianism. Life is, in fact, often equated with goodness itself, opposed to the evil of death. Once the virtue of life is established, the virtue of health can hardly be doubted, but health is also a virtue of its own, for life has significantly less virtue when overcome with illness.

Fire and Water

Here in California, we have two seasons: a season of water and a season of fire. The fire season generally begins when the rains cease, which is typically in mid-April—say, Tax Day. The fire season continues beyond the end of summer into the warm California autumn, until the rains return—around about Halloween.

I remember, as a matter of fact, the rains returning last Halloween, while trick-or-treating with the kids. I remember how warm that first rain was. It even seemed refreshing.

The old Gaelic year ended on Halloween, so I hear. In California, the return of the rains is obviously a big deal, but I’m not sure it ought to mark our new year (as though it represented a rebirth).

I say I’m not sure, but it probably should. It’s ironic because the leaves haven’t even fallen from the trees yet by Halloween, but one can watch the world being slowly reborn through the mild winter months. February and March bring progressively more glory, but it all begins with the first rain in autumn.

My doubt has to do with the role of the sun in all this. To base the rebirth solely upon the return of the rains seems to disrespect the importance of sunlight in bringing about life, but I suppose it’s obvious enough that this is all made possible by the fact that the sun is somewhat ever-present around here.