La Jolla, 1914. Robin and Una had been dreaming of starting anew in rural England since they were married a year before. They could afford to do so because of Robin’s modest inheritance, and they could expect more after the passing of Robin’s father, then 75 years old and with failing health.

In midsummer 1914, an unprecedented outbreak of organized violence struck Europe. By the end of that summer, a million people were dead, and the war was settling into a bloody stalemate that would last four years. This turn of events forced the young lovers to change their plans and move up coast to Carmel instead of England.

When Robin and Una Jeffers arrived in Carmel in summer 1914 [1], Carmel was already an established tourist attraction and artist colony, though it was nothing like it would soon become.

|

| Preble Grocery, 1910. Source (Harrison Memorial Library) |

Carmel had for 34 years been on the periphery of the Del Monte tourism complex. The Hotel Del Monte had been a central part of the business plan of the Railroad. In 1906, the great San Francisco earthquake and fire sent artists and art lovers south to Monterey and Carmel. Three years later came the Model T Ford, and the Monterey tourist trade was enjoying a sustained expansion. Famous artists such as Robert Louis Stevenson, Jack London, Mary Austin, Sinclair Lewis, and Upton Sinclair had recently spent time at the elite retreat of Carmel. Poet George Sterling and writer Jimmy Hopper had houses there. Pebble Beach Lodge was a popular destination for motorists. At the end of Seventeen-mile Drive, Carmel had several attractions of its own, including several hotels and a 9-hole golf course at Carmel Point. It also sported several shops, a lending library, a small movie theater, several churches, and of course the obligatory real estate office.

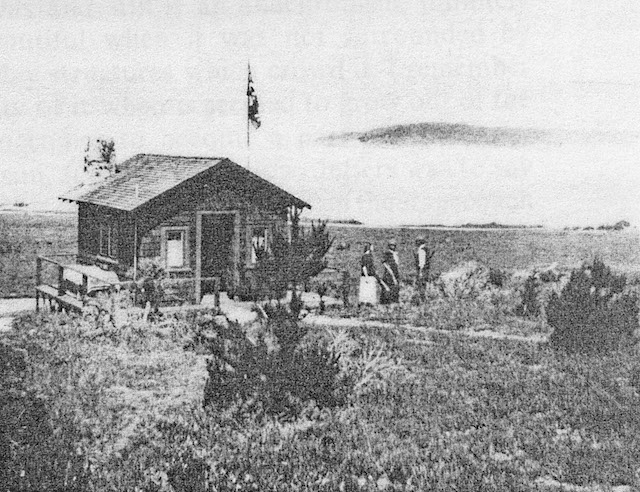

|

| Carmel Point clubhouse, 1912 (Harrison Memorial Library) |

The village was growing now that people could drive there. Carmel-by-the-Sea, it might reasonably be said, was conceived by an earthquake — or perhaps a fire, and raised on the internal combustion engine.

|

| Golfers at the future site of Tor House, 1914 (Harrison Memorial Library) |

Robin and Una moved into a cabin near the heart of of the fledgling town. They took many a walk through the Carmel woods and even out to the Mission and the Point. Though Una was not as inclined as Robin was to take long walks, she was no fainting daisy.

Three months after leaving his parents down in Southern California, Robin got word that his father had died. Dr. Jeffers had done more in life than anyone to shape Robin into an aspiring poet with a deep classical education. In death, the elder Jeffers would provide for his sons with an annuity that would finance Robin’s land purchases, a new car, his family, leisure time, and time for writing.

It may have been during their visit to Pasadena shortly after Dr. Jeffers’ death that Robin and Una purchased their car. It was a Ford Model T, likely a first-generation ‘T1’ [2]. They would make good use of their Ford, whether for shopping, for driving to Southern California, or for touring the countryside. The five years immediately preceding the war had seen the beginning of a cultural revolution in America. With the advent of the internal combustion engine and the assembly line, Americans were driving everywhere, and the Jefferses were no exception. Una, in fact, had enjoyed racing cars before she married Robin. These were days of mad motion.

After two years in Carmel and much ruminating about his inability to write worthwhile verse, Robin got a new book of poems published. It wasn’t much, but it was published. This was his first book of poems of his that a publisher would be willing to get behind. It received pleasant reviews but few readers. He would not get another book published for another nine years.

Una was entering her final month of pregnancy, so the two returned to Pasadena so that Una could give birth under the care of a trusted family doctor (under whose care their daughter’s life had been lost). Una had twin boys, Donnan and Garth, who though born together were very distinct from each other in size and temperament. Robin returned alone to Carmel to find a larger house. He found one about a block away from their cabin.

William Everson, a poet known to have a preoccupation with sex, conjectured that Jeffers, on the threshold of his thirties and being on his own for the first time in four years, must have had an extramarital affair or two before Una returned to Carmel with the twins. Jeffers’ racier poems from a year later (Fauna and Mal Paso Bridge, 1918) make this seem plausible, and he was a man after all, yet such plausible but merely alleged behavior would seem to have been of little consequence to the arc of the poet’s career. [3]

|

| Robin and sons, Trethaway House, 1917 (Tor House Foundation) |

Meanwhile, in a world very far away, the Great War raged on. A few months after the Jeffers twins had been born, the United States entered the war. Robinson Jeffers was without an occupation other than writing, and at that he had been a failure. He had few obligations to keep him from going to war, but he hesitated. He was not a conscientious objector. He’d mentioned the war here and there in his poetry, but nothing that would qualify as anti-war. Over a year after the US entered the war, he would enlist the air corps, only to find that he was too old for that particular service. He then enlisted into the balloon division, but the war ended before he could serve. By the time he turned 32, Jeffers had little to show for himself other than his offspring. That would soon begin to change. —Next—>

––––––––––

Notes:

1. Una’s letter dated October 3, 1914 indicates that she and Robin had been in Carmel for a month at that time.

2. The purchase may have been as late as the following summer. See Una’s diary, Feb 1, 1915 and August 25, 1915.(ed. Robert Kafka, Jeffers Studies, Vol 7 No. 2, Fall 2003)

3. Everson’s conjecture gave rise to a Freudian doctrine that extramarital sex inspired a great turning point in Jeffers’ career. Advocates of this doctrine point out, for instance, that Jeffers’ poem Mal Paso Bridge (1918) doesn’t rhyme (the poem even boasts of this); but unwillingness to rhyme was far from revolutionary at the time. Rhyme or no rhyme, the quality of Jeffers’s work failed to show significant improvement for over five years after his solo time in 1916/17 (see dating of Continent’s End, CP V:61). Those who insist that art imitates sex might do well to consider that Jeffers had already enjoyed ample wild living while attending USC. The fruit of those misadventures was indisputably inconsequential.